Like us on Facebook for all TEIC news and updates about our teachers in China TEIC Facebook page

Game ideas for primary school students

Chinese primary students like games, especially competitive ones!

Megan Jarman has recently returned from a year teaching at primary school Shanghai, and here she shares some of the games that her students liked.

Body part flashcards

Before the class prepare a set of flashcards in the shape of different body parts and write a certain number of points on the reverse. Attach these to the board during class as you go over the vocab with the students, gradually building up the full body. Then students must compete to raise their hand the fastest after a countdown. The quickest student can identify a body part using the target language. If they are correct they come up to the front and remove that body part to find out how many points they have won for their team.

Pass the bomb

Students pass an object along their team as quickly as possible while the teacher counts down from 10. When the bomb “explodes” at 0 the student who is holding it must answer a question. Alternatively one team will pass the object down the line, each giving a relevant vocab word when it reaches them. No two words can be repeated. Each team will be timed. The quickest time wins the points.

What do you hear?

A representative from each team will go to the blackboard. The teacher describes something and they must draw what they hear. For example “The dog has a long tail and 3 legs”. A point will be awarded for each correct part of the drawing. Alternatively the students, in their teams, can be given a drawing of something with distinct features which they must describe it to the teacher to draw. Afterwards the drawings can be compared.

Rearrange the sentence.

Each team will get a set of word flashcards. In each round of the game 2 teams will have a number of representatives come to the front of the classroom. The students have to answer a question by making the sentence with the flashcards. For example “is it hot in winter?” “No it is cold”. Each one must stand with a word in the correct order. Get the rest of the class to read the sentences out loud to verify if they are correct.

Memory test.

This is a simple vocab memory game. Firstly stick the set of vocab flashcards on the board. Drill with the class getting faster and faster. Then draw a circle around one of the flashcards and remove it. Repeat the drill including asking the students to recall the missing card from memory. After each round remove another flashcard until you are left with nothing but circles on the board. Individual students then have the opportunity to come and recite the vocab depending on what circle is being pointed at.

Missing item.

Students pick out items of a bag to recap the vocab and target language as a class. They then place the items in a tray or flat surface. Students will then have to close their eyes while an item is removed from the tray. They will then have to name the item that has been taken.

Socialising with staff

The local teachers in your faculty will likely have at least double your work load, spending most of their time running to and from classes, meetings or training days. Because everyone works such long hours there are likely to be strong friendship groups within the school, almost like family.

If you are lucky enough to be invited to get-togethers where teachers let their hair down, it’s really important to go along and make a good impression. It doesn’t matter if your Chinese is terrible, all that matters is you go along, smile and be open and enjoy yourself. In the past it has been common for foreign teachers to join their colleges to karaoke, bowling or cards nights (pictured below), the cinema, or shopping.

What we look for in applicants & what to put in your CV and cover letter

Teaching English in China is all about thinking on your feet, having fun, being comfortable with public speaking and enjoying working with children and young people.

Teaching in China can be immensely rewarding but initially you may feel like you’ve been thrown into the deep end, as you start teaching shortly after arriving in China.

If you are interested in applying it would be good to highlight the following things in your CV:

* experience working with children

* experience with public speaking

* time spent working or studying abroad

* leadership positions

We’ve been very impressed with recent applicants, in the past few weeks we’ve spoken to people who: studied in Korea for a year, worked in the armed forces and instructed the Afghan army, presented radio shows, worked as fundraisers, coached jiu jitsu, are doing a PGCE, worked as student ambassadors and as lifeguards.

Whatever it is that you can bring to the table and can make you a fun, engaging teacher who can contribute to the education of students in China is very welcome.

To apply send a CV and cover letter to info@teach-english-in-china.co.uk

Q & A about teaching English in China

As part of a university project, former summer teacher Oliver Palmen asked TEIC Director Arnold Vis a few questions about teaching in China, the attributes needed for it and what’s gained by teachers in the process.

1. Firstly, when did you become involved in Teaching English in China?

I got involved with TEIC in 2005, a few years after I returned from teaching in China myself.

2. Why did you feel that a service like TEIC was needed?

I found a job in China online at the time, and I had a great time at my school. However before I went I felt unsure about what I was about to do, what would be expected of me and how things like the visa process worked. Whilst in China I also found that certain schools don’t have the best reputation, so I felt there was a need for a company that could help applicants better understand what teaching in China was about before they went, and help them find jobs at schools with a good reputation.

3. What do you look for in candidates for travelling over to China to teach English?

More than anything I look for people who think they’d have a good time with the teaching job. As a teacher in China the students will not always understand exactly what you are saying at all times, so it’s very important you have fun with it and create a good atmosphere in class. Generally I look for people who have some experience with what I consider the key parts of the teaching job: public speaking, being creative & thinking on your feet, and building rapport with the students.

4. How easy is it to find people with the right attributes for teaching?

In recent years I’ve been extremely impressed with the level of the candidates we’ve interviewed, and the schools have been very satisfied with their work. I think that’s been down to the videos, stories and pictures that teachers have provided over the years. I strongly recommend that applicants research the experiences of other teachers on our programme over the years, as I’ve found that it’s one of the best ways of ensuring people applying have a realistic sense of what it’s all about before they sign up for the programme. I feel this has played an important role in recruiting the right candidates.

5. What do you think helps when working as a teacher?

Mainly enjoying it as I mentioned, and remembering that making the occasional mistake is fine. The opportunity to practice with you, and to gain more of an understanding about life in other countries is invaluable for students in China, even if you don’t have lots of teaching experience and get everything right at all times.

6. Do you think teaching for two weeks is long enough to really experience China, or would you recommend a longer course, such as the two month placement that I went on?

Teaching is very intensive, so 2 weeks can be enough to experience lots of things you’ll remember for a very long time and give you insight into working as a teacher and life in China. A summer placement is a first experience and many people who worked on the summer scheme have gone back to China for work and studies after graduating.

7. Would you suggest having some time to travel and explore China while over there?

Definitely. China is such an interesting country that is changing all the time. On our placements you with a group of people who are all in the same boat, so I’d definitely recommend travelling afterwards.

8. What do you feel that teachers gain most from their time teaching abroad?

I think that depends on what you were looking for in the first place. I have an interest in politics and social science, so for me personally the thing I gained most was an understanding about life in China an insight about how young people in China view the world. I loved having conversation with my students about things like their views of other countries and what they wanted to do in the future. For other people the thing they gain the most may be the teaching experience or the friends they meet in China. Generally speaking I’d say an experience like living in China, so far out of your comfort zone, makes you a more resourceful and rounded person.

Paid teaching in Shanghai: first 2 months

NEW VIDEO: Helena Sykes put together this incredible video about her first 2 months on her long-term paid teaching position in Shanghai that started end of August 2014. Before arriving in Shanghai Helena spent 2 weeks in Beijing at the Beijing training camp. The video captures her entire journey, from leaving the U.K., to the Great Wall to teaching classes in Shanghai

How to survive as an expat in China

NEW VIDEO: Summer teacher Shane Voigt provides advice about adapting to life in China, including getting connected, handsigns, talking to taxi drivers, compliments…. and much more.

Exercise in China

Gyms can be found across the country, but they have yet to become a regular part of local life. Most use parks with ‘out door gyms’ (a few pieces of exercise equipment), or dance their with partners/big groups. Subsequently, they can be a little expensive. However, as with most things in China, they can be bartered for!

Pictured below is H3, a gym in the Jiading District of Shanghai. Membership fees are outlined as £40 a month, but three of our teachers got that price down to £25 (not that different from the cost of a Western gym) In smaller provinces, membership can be around £80 for the year. The gyms contain everything you’d find in a Western gym like weekly dance, combat and cardio classes. Many of our teachers join as a way to keep fit and meet new people.

By Helena Sykes, teacher in Shanghai

The Phases of Cultural Adjustment

Preliminary stage:

This phase includes awareness of the host culture, preparation for the journey, farewell activities.

Initial euphoria (sometimes called Honeymoon):

The initial euphoria phase begins with the arrival in the new country and ends when this excitement wears off. In this phase, discovering the new culture is an exciting adventure. The newcomer enjoys learning about the culture and partaking in local customs, including food, entertainment, sights and activities. This stage may last several months or may end quickly.

Irritability (or Hostility):

During the irritability phase you will be acclimating to your setting. This will produce frustration because of the difficulty in coping with the elementary aspects of everyday life when things still appear so foreign to you. Your focus will likely turn to the differences between the host culture and your home, and these differences can be troubling. It may be hard to reconcile how you need to behave in the host culture with your core values and beliefs. Sometimes insignificant difficulties can seem like major problems. One typical reaction against culture shock is to associate mainly with other Anglophones, but remember, you are going abroad to get to know the host country, its people, culture, and language. If you avoid contact with nationals of the host country, you cheat yourself and lengthen the process of adaptation.

People react differently in this stage. Some become angry at the host culture and see every little difficulty as an example of the inferiority of the culture. Others become withdrawn, sad, lonely and depressed. They may find it hard to do the smallest tasks. Some become ill, with real symptoms, but no identifiable cause. Some may even lash out at others from their own culture.

If you see other foreigners going through this stage, tread carefully. People in culture shock do not like being told that they are in culture shock. They see it as a belittling of the very real problems they may be having. You can help by listening and letting them vent. If someone is withdrawn, try to make contact with them. Invite them to do things with you. Encourage them to write or call loved ones at home. Try to help them find something they can enjoy about the new culture. If the person in culture shock becomes aggressive with you, don’t engage in arguments or debates. Stay away until they have calmed down.

If you feel yourself going through culture shock, keep in mind that it will get better. You will eventually find ways to cope with the differences and feel more at home. Stay in touch with friends and family- email is wonderful for this! Tell them your experiences- funny, sad, or annoying. Whatever you do, don’t make drastic decisions while in this phase. Many people give up on their adventure and go home rather than waiting it out until they feel better. Ten years from now, you’ll still be telling people about your experiences in China, long after the minor frustrations and irritations are forgotten.

The honeymoon and hostility stages are not separate and well-defined. You may be having a great time one day, miserable the next, and fine the day after that. Small problems can throw you into a culture shock episode, but you may go in and out of honeymoon and hostility for some time.

While the length of these stages varies for each person, there is a tendency to go into the irritation stage at about 3 months. This seems to be the time when the newness has worn off, and there are few new experiences to bring you back into honeymoon. If this happens, try to discover something about your surroundings that you haven’t already experienced.

Gradual adjustment:

When you become more used to the new culture, you will slip into the gradual adjustment stage. You may not even be aware that this is happening. You will begin to orient yourself and to be able to interpret subtle cultural clues. The culture will become familiar to you. Every day tasks will no longer seem so overwhelming and you will have found people, places and activities that offset the minor irritations. You will also find ways of adapting to the new culture without letting go of the most important parts of your own culture.

Adaptation and biculturalism:

Eventually you will develop the ability to function in the new culture. Your sense of “foreignness” diminishes significantly. And not only will you be more comfortable with the host culture, but you may also feel a part of it. Once abroad, you can take some steps to minimize emotional and physical ups and downs. Try to establish routines that incorporate both the difficult and enjoyable tasks of the day or week. Treat yourself to an occasional indulgence such as a favourite meal or beverage, or a long talk with other Anglophones experiencing the same challenges. It can be oddly reassuring just to find a familiar fast food place and have your favourite meal. Keep yourself healthy through regular exercise and eating habits. Accept invitations to activities that will allow you to see areas of the host culture outside the university and meet new people. Above all try to maintain your sense of humour.

Re-entry phase:

The re-entry phase occurs when you return to your homeland. For some, this can be the most painful phase of all. You will be excited about sharing your experiences, and you will realize that you have changed, although you may not be able to explain how. One set of values has long been instilled in you, another you have acquired in the host country. Both may seem equally valid.

From TEFL course (part of standard service option for long-term paid teaching September start)

10 tips about living in small cities in China

Faye Shaw is teaching at a state school in Lianyuan, a small city in Hunan province. She offers 10 tips about getting used to life in smaller cities in China.

1. When you first arrive in China, it’s likely to be a busy time. On our first day in our city we were taken out to breakfast, had a trip round the supermarket, then lunch, with a brief respite at the apartment before we were whisked away to go swimming in a nearby lake, and were then fed again. It’s tiring, but it’s good to be kept busy at first, getting to know your new colleagues, and when you finally get time to yourself you’ll appreciate it so much. Do put your foot down though and say no to an invite if you have planned to Skype family. And this is actually a good go to excuse should you ever have to get out of something.

2. Try to make your apartment as comfortable as possible; typically the working hours are low so you may end up spending a significant amount of time there. Take a day to get it as clean as you can and blast it with bug spray, then put up photos from home, or any other bits you’ve collected to make it a little bit more homely.

3. Make friends with the Chinese English teachers at your school. Invite them out to your cheap local restaurants or to play badminton. If you’re struggling to find other English speakers in the area then other teachers can be an important part of your social life. They may also be able to help with some things that your go-to person might not be as quite adept at- for us it’s anything to do with the internet, so one of our friends helps us to book train tickets and buy things online.

4. Learn Mandarin! Those living in a major city may find more people willing to speak to them in English, but after a while you may find you have no choice. It’s easier than you might imagine not being able to speak the language at first. Pointing gets you through the basics, and locals may tolerate it for a while seeing as you are a novelty, but living in a small town is the perfect opportunity to learn. If your school doesn’t offer lessons, then do an online course, (Michel Thomas is quite a good one: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Mandarin-Chinese-Beginners-Michel-Program/dp/0071547363). The spoken language of Mandarin isn’t actually too complicated and you can soon learn enough basics to use in shops, restaurants, and to explain to curious locals where you’re from and why you’re here. If the city you live in speaks with a strong dialect then use travelling as an opportunity to practice. Your students will always be happy to teach you new words so utilise them as well!

5. Be nice to the locals! You’ll probably end up frequenting the same shops and restaurants so always be polite.

Market in Lianyuan

6. Travel. While you’re in China try to see as much of it as possible. You don’t know when you’ll come back again. The big trips break up your time in China, and have smaller trips planned for the weekends to other nearby cities where you have friends from orientation, or know there are lots of other westerners. These trips are something to look forward to and make the weekdays go quicker because it gives you more to think about and organise lesson planning wise.

7. But do explore your city. Its size means you can’t wander too far and get horrendously lost. You might find some interesting places, and best of all might find some new joints to eat in.

8. If you have a lot of free time, use this as an opportunity to get a hobby or develop a skill. Learning Mandarin is an obvious one. I had never set foot in a gym until I moved to China and now I go almost every day. I’m also really, really good at naming countries capital cities… It’s also a good time to binge watch a TV series and read the books you’ve been meaning to, (books or a Kindle are a good idea because there is a tendency for the electricity to cut out more often than we’re used to at home).

9. Ignore the stares. I’m still not used to this eight months later. It’s hard to comprehend coming from such a multi-racial society in the UK, but in China you may be the first foreigner somebody has ever seen. It can be annoying, imagine struggling with chopsticks or shovelling noodles in your mouth to then see a table full of people staring, and maybe even taking pictures. There’s nothing you can do about it so it’s best to embrace it and smile. It’s a situation you’re unlikely to find yourself in again. Failing that, on the days when you’re feeling, basically pretty ugly and don’t want to be noticed, try to ignore it.

10. Anytime it starts to get tough, remember that what you’re doing is unique, and there won’t be many people with the same stories or experiences you have at the end of it. A lot of people wouldn’t be able to do what you’re doing at all- at least that’s what people keep telling me.

By Faye Shaw

Learning Mandarin

Lewis Tatt lives in Shanghai and he’s been teaching English in China and studying Mandarin for several years. The coming weeks he’ll talk about his experience learning the language, in terms of speaking, listening, reading and writing.

Today’s first instalment– Speaking Chinese:

The sounds:

To point out the obvious, Chinese is phonetically different to English. It therefore would be advisable to find a private teacher to help you at first, although this is not essential. A good alternative would be to use software such as Rosetta Stone or simply listening to the recordings that come with any good textbook. What’s important is that time needs to be spent listening to Chinese, because if you don’t even know what the Chinese language sounds like you definitely won’t be able to speak it correctly. Personally I didn’t learn pinyin when I began learning Chinese because, as a native English speaker, I was concerned that using pinyin as my pronunciation reference from the very beginning would run the risk of me thinking of the Chinese language in terms of English language phonemes. Pinyin is extremely useful as a guide for how to pronounce words, but it is important to understand that the letter “R” in pinyin represents a sound very different to the “R” in English. The more you listen to Chinese the more familiar you will become with the sounds. Repeated exposure to spoken Chinese and a considerable amount of listening are very helpful.

The tones:

Chinese has a reputation for being difficult because of “the four tones”, and almost every English-speaking learner has at times struggled with this aspect of pronunciation. Those self-studying usually have a more difficult time, not because the tones are so difficult, but simply because of the tendency to be intimidated by the tonal aspect of pronunciation and as a result neglect it. I have met many self-learners who believe they can say a sentence in Chinese but when asked what the correct tones are for each word it turns out they do not know. The simple fact is that speaking the correct tones is infinitely more difficult if you don’t even know what the correct tones actually are. There is no point even trying to say a word in Chinese if you haven’t learnt the correct tone. You might be able to guess, and there is a one in four chance you will get it right. But there is also a three in four chance you will get it wrong, and each time you pronounce the word wrong you are teaching yourself incorrect pronunciation, which will take more time to correct that the amount of time it would have taken to learn the correct pronunciation in the first place. There is one very simple fact with speaking Chinese: if you learn a word but can’t remember what tone it is then you haven’t learnt that word.

Learning the tones is actually not difficult at all, but it takes time and can be tedious. In order to remember the tones I would write the tone marks above each word/ character whenever I write it or see it. Most elementary level textbooks have the texts written in both pinyin and characters. Read the pinyin text then read the characters text and write all the tones above each character. Then look back at the pinyin and see if the tones are right. Circle each character you wrote the wrong tone for so you have a strong visual indication of the frequency with which you put the wrong tone. Hopefully you should be able to see that frequency go down as you study more. Similarly, every time you write a sentence write the tone marks above each word and then check them in the dictionary. It’s time consuming, but it works. You can also try to be more creative, perhaps making flashcards with the pinyin/character on one side the tone on the other. You can play simple games in which you match words/characters separate them into groups on the basis of tones, flipping the card over to reveal the correct tone after you have guessed it. However you go about learning the tones, it is only when you know the correct tones for a word that you can then attempt to pronounce that word.

The speaking:

You need to speak lots. Saying the word once is about as useful as going to the gym and doing one pull up. You might learn how to do a pull up but you won’t do much to exercise your body. Similarly, you might learn how to say a word but you won’t exercise the part of your brain processing these new words. You need to give your brain a workout, so listen to the recording that comes with the textbook, then record yourself speaking and listen back to it. It can be painful listening to your own voice, particularly when it’s mauling a foreign language, but it has to be done. If your hair is in a mess it is difficult to correct without a mirror to see what it looks like. If your pronunciation is a mess it is difficult to correct without a voice recorder to hear what it sounds like. A simple smartphone app will work perfectly. Record yourself, listen to yourself, listen to the textbook recording, record yourself, listen to yourself again. To increase fluency simple pattern drills are a tried and trusted technique. An English sentence pattern drill might be as follows: “I am a student. He is a student. She is a student. My mum is a student. My dad is a student. My dog is a student…” It doesn’t actually matter whether you, your mum, or indeed your dog, are students or not. What is important is that you speak these sentences out loud so that you are able to use the sentence structure without having to consciously stop and think how to say that sentence.

The rhythm:

One source of immense amusement for many Chinese is how native English speakers will “sing” Chinese. Whenever native English speakers speak Chinese they will “sing” everything. Many Chinese people will go as far as mimicking this way of speaking whenever they talk to someone they believe to be a foreigner. This is because spoken Chinese has a completely different rhythm to spoken English. If you maintain the rhythm of spoken English when speaking Chinese the result is that, to a Chinese speaker, you sound like you are trying to sing. Even more problematic is that maintaining the rhythm of spoken English when speaking Chinese makes it almost impossible to say the correct tones.

There is one very simple way around this. Speak. One. word. At. A. Time. This might result in the speaker sounding like the Chinese equivalent of Stephen Hawking’s robotic voice, but no one ever had trouble understanding the pronunciation of Stephen Hawking’s robot voice. By contrast, lots of Chinese people do have trouble understanding foreigners with terrible pronunciation. The intonation and rhythm of spoken Chinese is very different to that of English. Furthermore, each syllable in Chinese is a separate word, so completely breaking down the rhythm of your natural speaking and pronouncing clearly each individual syllable when you speak Chinese will result in Chinese people considering you to have a surprisingly clear and “standard” pronunciation. You might feel stupid at first, but to a Chinese speaker you will sound far less stupid that someone who is attempting to “sing” Chinese with incorrect tones. Chinese is very different to English in terms of tones, intonation, rhythm and phonemes, so if you don’t feel stupid when you’re speaking it then you’re almost certainly not pronouncing it right.

By Lewis Tatt

Sample lesson plan: Tongue twisters

What are Tongue Twisters?

*Puts together sounds in a confusing way

*Challenges your pronunciation

*Super fun!

How to play:

*Get into rows (your row is your team)

*I will show you some tongue twisters and practice how to say them with you

*You and your team will have 2 minutes to prepare

*Each person in your team will stand up, say the tongue twister, and sit down in order

*Try not to make any mistakes!!

*I will time you – the team with the fastest time gets a point!

Tongue-Twister #1

Tongue-Twister #2

Peter Piper the pickled pepper picker picked a pack of picked peppers.

Tongue-Twister #3

She sells seashells by the seashore

Tongue-Twister #4

Willy’s real rear wheel

Match up these words into pairs. Sound them out. Which ones have the same sounds?

*Meat

*Fun

*Hair

*Blue

*Such

*Glue

*Scared

*Feet

*Run

*Much

*Brother

*Glum

*Jump

*Bull

*Sit

*Thump

*Mother

*Full

*Hit

*Drum

Lesson By Emma Toll

Cost of living during a summer internship in China.

Helena Sykes worked in Haining last summer on the summer internship, and told us about her spending during her time as an intern.

What the school provide:

*Helena stayed in a nice hotel that the school paid for. She shared a big room with a fellow female intern, and both had double beds in an ensuite room.

*The school also paid for all her meals.

Breakfast would be rice, noodles, and fruit

Lunch and dinner would be similar: Fried meat, stew, Rice and vegetables.

What she spent her money on during her internship:

*Trips to the supermarket: about every 4 days a group of interns would go for a big shop at the local supermarket and buy things like:

Snacks for in the rooms

Water

Sweets for the students in class

Beer for film nights at the hotel

That would cost about 100 to 150 RMB (£10 to £15) every 4 days

*Eating out: because the meals were very similar every day, at times she ate out for dinner. Mostly that wold be a local restaurants where a group of interns shared lots of dished for about 20 RMB (or £2) per person.

Sometimes it would be a Western oriented restaurant like KFC or Pizza Hut, where a smaller meal would cost more, about 30 RMB or £3

Other regular costs were:

* Water(daily) large bottles 3 RMB or 30 pence.

* Taxis: She lived about a 15 minute walk from the teaching site, but because of the heat a group of interns would regularly take a taxi and take turns paying the 15 RMB (£1.5) fare,

All in all Helena’s spending during her month comes to about £135.

The school offers pocket money of £120 per month.

We advise interns to budget for £200 per month to be on the safe side.

Not all schools provide all meals, and other spending in terms of going out and transport may vary as well.

Accommodation is always fully paid for by the school.

Cost of living in a small city in China

Faye Shaw started teaching at a Middle School in Lianyuan, Hunan province in September 2013.

Lianyuan is a small city by Chinese standards, with a population of about 1 million.

She is currently on her winter holiday and briefly returned to the U.K. She joined us at Huddersfield University yesterday and told us about the cost of daily life in her city.

At her state school Faye is paid 5000 RMB per month, which is £500 in pounds.

Her accommodation is provided for free (she shares a large apartment with another teacher from the U.K. from our programme).

Her daily spending on food is limited; she usually has lunch at the school cafeteria, where food was provided for free the first month, and she now pays 4 RMB per day (40 pence in pounds).

For dinner she usually goes to a local noodle bar, where she eats noodles for about 10 RMB (£1).

Faye estimates that she spends about 1500 RMB per month in Lianyan (£150) on living expenses.

Because Lianyuan is a small city she goes to Changsha about once a month for a long weekend.

Changsha is a big city and with more expat oriented bars and restaurants, which are considerably more expensive than the ones in Lianyuan. She would also shop for clothes in Changha. Including accommodation a long weekend there costs about 1000 RMB (£100).

So including trips she spends about half her salary per month, and saves the rest.

These prices apply to a small city like Lianyuan, food prices are higher in bigger cities like Wuhan.

Mandarin text book review, by Lewis Tatt

Lewis is a teacher in China and has been studying Mandarin for years

For those intending to become long term learners of Chinese who want to reach advanced level and understand more cultural aspects relating to the language, particularly if they intend to begin their study whilst still outside of China, there are two particularly useful textbook series that can be used as an entry point:

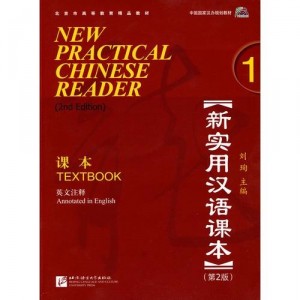

New practical Chinese reader

New practical Chinese reader is a series of six textbooks from absolute beginner to upper intermediate. Textbooks 1-3 are beginner and elementary level. Textbook 4 crosses over to the intermediate level, which is covered by textbooks 5-6. The series was designed by Hanban, which is the government department responsible for teaching Chinese as a foreign language and running the HSK exam system. This is the standard university textbook at many universities in the UK, America and Australia.

This book is not necessarily the best option for those wanting to learn Chinese quickly, but for learners aiming to reach complete fluency in all areas of reading, writing, speaking and listening this series is highly recommended. The first four textbooks follow a group of Chinese and non-Chinese characters, and come with DVD videos of the dialogues. Books 5-6 are non-character based lesson texts suitable for more advanced learners who have progressed beyond language required for everyday conversation.

The acting in the videos is bad to the point that it can be funny, but if anything the resulting amusement helps the learner to remember vocabulary and sentence structures. Lesson texts often emphasise cultural aspects of China, with the characters discussing issues as diverse as why Chinese people speak loud in public places and the one child policy, as well as mildly amusing scenes such as one in which one of the young male characters, having married a Chinese girl, becomes confused as to how he should refer to his parents in law. One of strength of this series is the relatively high frequency with which grammar points and sentence structures reappear in later lesson texts, enabling them to be remembered more easily. However, some chapters contain low-frequency vocabulary that learners may not find useful at pre-intermediate level.

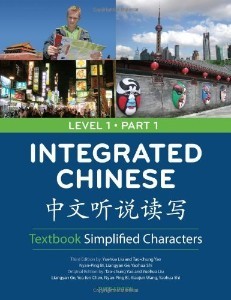

Integrated Chinese:

Integrated Chinese is the most widely used Chinese language textbook series in American universities, and is also widely used in the UK. As with New Practical Chinese Reader this series is aimed at giving the reader a wider understanding of China, not just language learning, and every chapter has useful cultural notes for those new to the country. Again, similar to New Practical Chinese Reader this series has a core textbook with supplementary workbooks. The series has a total of four textbooks that are intended to cover two years of university study, which should leave the student at a low intermediate level not as high as New Practical Chinese Reader would with its six textbooks. The series is Taiwanese in origin and therefore comes in simplified and traditional character editions. It is important that anyone planning to travel to mainland China should make sure they pick up the simplified character edition if they decide to use this series.

The lesson topics featured in Integrated Chinese are in many ways more useful to everyday situations than some of those in the New Practical Chinese Reader series. The audio recordings usefully come in three different speeds; slow, medium and fast, and the third edition now includes DVD recordings of lesson texts. The grammar and language explanations are very clear and, although opinions vary from learner to learner, this series overall is perhaps slightly more enjoyable to learn from New Practical Chinese Reader. The downside is that, unlike New Practical Chinese Reader, it is not written to the HSK exam criteria and is unavailable at bookshops in mainland China. Integrated Chinese also features some vocabulary items that would be used by Taiwanese but not mainland Chinese, and thus will sound strange to mainlanders (for example using fan to denote a country’s food when mainland Chinese would say cai.) One particularly bad element in the second edition of this series was how the first textbook explained the phonetic sounds and tones of Chinese in an intimidating way that made the language sound far more complicated than it really is. Without a teacher such opening chapters in any series are often of little use to someone self-studying.

For those who are wanting to progress as quickly as possible and are focused on just developing their language ability the following series are easily available in China and worth considering:

对外汉语 (duiwai hanyu):

The fact the covers of this series of textbooks contain no English can perhaps be seen as an indication of how they take the readers attempts to learn the language quite seriously (the title duiwai hanyu translates as “Chinese for foreigners”.) This series is widely used at both universities and Mandarin training schools in China and covers the basic language up to third year university level. Each level in the series comes as a core textbook with separate listening, speaking and reading textbooks. These textbooks lack much of the cultural aspects, interesting presentation and extra learning resources featured in other series’ commonly used in universities outside China. However, despite the slightly less enjoyable learning experience the series arguably results in a quicker language progression.

As with any textbook each lesson dialogue is based on a particular context or topic, such as ordering food or visiting the post office. Usefully each level in the series re-visits the same topics featured in the previous textbook, reviewing the former textbook’s vocabulary and grammar whilst introducing more advanced grammar and vocabulary items. By the end of the series the reader should be able to confidently communicate in a wide range of practical everyday situations.

Because the series is split into separate textbooks the learner can choose to focus on the aspects they want to progress most in. For example, if the reader is not so concerned about developing their reading skills they can just work though the main textbook and the listening book. Vice-versa, if the learner has already reached a high conversational level but has neglected their reading they can purchase the reading textbook separately and work through it. One downside to this series is that, due to the speed at which it progresses, the reader can sometimes find the level too difficult and/or become frustrated, particularly if entirely self-studying without access to a Chinese teacher.

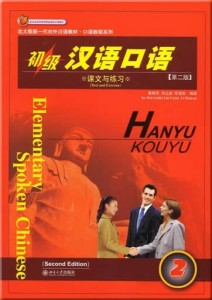

Spoken Chinese Series:

This is a very good series of textbooks for developing the learner’s ability to communicate orally and has six books in total, two for each level (elementary, intermediate and advanced.) There are also two other textbooks that act as crossover points between the three levels

Being a spoken textbook series the lesson texts up to intermediate level are based entirely upon dialogues between a small set of friends studying and living in China. The advanced level textbooks introduce non-dialogue based texts alongside the dialogues, whilst the “quasai-advanced” textbook, which feels like an add-on to the series, strangely drops the dialogues completely. The texts are not only practical but also interesting. For example in one dialogue one of the female characters questions a friend about the boy she saw her with, thinking it was a secret boyfriend, but it turns out to have been her brother. The series is full of colloquial expressions that will not only make it easier to communicate verbally, but also make the learners speaking sound more natural. The voce acting in the recordings is also not bad, bringing the dialogues to life and making it easier to study, whilst the grammar explanations are clear and simple.

The downside to this series is that although it assumes the reader is also learning to read and write it does not itself feature reading and writing exercises. At Chinese universities this textbook is often used for oral classes with other dedicated textbooks being used for reading and writing classes. Once the student knows how to write Chinese characters this series can be used alone but time needs to be spent practicing writing the sentence structures and new vocabulary that are introduced. Also, some of the spoken phrases in this series are slang phrases that are particular to northern China and not used in areas such as Shanghai or Guangzhou.

Due to the oral nature of this this series any learner using this book alone will of course be able to speak well and have little trouble reading spoken Chinese, such as text messages and social networking site posts. However, relying on this series alone they will have trouble reading more formal non-spoken Chinese, such as newspapers and magazines.

By Lewis Tatt (Lewis worked in Wuhan through Teach English in China between 2010 and 2012, before moving on to work for a primary school in Shanghai).

LESSON PLAN: Topic–Beginner Idioms (Theme: Animal Idioms)

Goal: Enhance previous knowledge of idioms and practice the use of idioms in conversation.

Introduction Game: I have not had some of the beginner class yet so I’d like to start with a name game.

Name Game – Count the number of letters in your first name. Find a person in the room with the same number of letters as in your name (if need be you can reduce the name to a nickname. For example, Joseph could become Joey or Joe.). The goal is to find a partner as quick as you can. When the room is paired off the pairs introduce each other.

Warm Up Game: Write down as many idioms as you know. After 2 minutes of writing I’ll have them refer back to that list to see if they could write down the meaning or the appropriate context for those idioms. Go around the class to share idioms – any involving animals I’ll put up on the board to introduce today’s theme – Idioms used with animals.

Idioms to be Taught:

Curiosity killed the cat

Raining cats and dogs

Til the cows come home

Go to the dogs

To take the bull by the horns

A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush

A bull in a china shop

To be stubborn as a mule

To be as slippery as an eel

To be as strong as an lion

To be as proud as a peacock

To be as blind as a bat

To be as cunning as a fox

To be as free as a bird

To be as brave as a lion

To be as wise as an owl

Sounds Game: I will ask for a volunteer to come up to the room and hand them a slip of paper. They will read the first part of the idiom and act or sound out the animal part. For example, “To be as brave as a lion” they would say “To be as brave as ……” then let out a ROAR or make a ferocious sound to indicate to the class that the appropriate animal is a lion. We will go through first 15 in the list above.

As we go through each idiom, I will ask if they know the meaning and if not give a definition.

Reading: I will read a short idioms story found on that involves animals. I have tweaked the story to include some of the idioms we have already learned and there are a few more intertwined that I hope they will pick up on.

They should identify as many as possible and write them down as I read the story. We will go through them after.

End Game: I will provide them with paper and coloured pencils and ask them to draw out one of the idioms we learned.

Game by Arielle Bean (summer teacher in Shaoxing in 2012). this game and many more will be part of the new Lesson Plan Library that will be accessible to all applicants on the standard serviced option soon.

Strangers in a Strange Land: Life in a Chinese Expat Community

When moving to live and work in a country like China, the expat community you become part of can play a big role in determining how easy you find it to integrate into your new society and how much you enjoy your stay abroad. Unless you have pretty good Chinese before you arrive, you will probably find yourself spending a lot of time with the other foreign teachers in your area and even if you do have Mandarin, you will still feel the need to speak to people in your native language every now and again. This is a particular issue in Wuhan, where I live, as basically no-one speaks any English so to talk to anyone other than expats I have to rely on my Chinese. Often, although my Chinese isn’t too bad, all I want to do is hang out with some friends without having to constantly be concentrating on translating what everyone else is saying in my head. This means I spend a lot of time with other foreigners, which has given me an interesting look at what it’s like to be one of a small number of expats in a very foreign place. It’s inevitably a little weird at first – you don’t know each other, but you are kind of forced to get to know and like the other expats simply because they are the only people in the city who speak your language. Also, because your expat group will be pretty small, there will probably be times when it really gets on your nerves. But, in spite of this, relationships between expats tend to be pretty close – the friendships I have with some other teachers out here are as close as any I have ever had.

The first way in which the expat community in Wuhan had a significant impact on my life out here was that it made my period of settling into life in China a hell of a lot easier than it would otherwise have been. When I first arrived the Chinese company I was based with wasn’t all that helpful and didn’t give me all that much help beyond sorting me out with a place to live. I had to figure out pretty much everything myself from how to get to work to where I could buy stuff for my new place. Without having other expats to ask about this, I would have struggled a great deal with this kind of thing. However, my company had asked me to let one of its more experienced teachers stay in my flat until he could find a place of his own. He took me and my flatmates for a drink with some of the other teachers who had been in Wuhan for a while and I got to know a good portion of the group then. Over time, I they introduced me to other people they knew and I met even more new people through the bars and other places they introduced me too. Because we spent time together socially early on, I was in a position to ask them for help when I needed it. Having other English speakers to ask about my new city made a huge difference to how easy I found it to settle in Wuhan. I found almost all the expats living here to be very friendly and willing to go out of their ways to help me out, which I really appreciated. I think that because everyone who makes this kind of move has experienced how tricky the first weeks and months can be, so are naturally inclined to sympathise with a confused new arrival. I certainly was – when a group of new teachers arrived early this year I did my best to help them out any way I could because I remembered how difficult I, and everyone else who arrived at the same time as me, had found to get used to life here. If I was pushed to give what I thought was the most important aspect of becoming part of an expat community in China, it would be that it provides a support network that, in my experience, you are unlikely to receive from your Chinese company.

Although I certainly can’t generalise this to all expat communities as this part is strongly dependent on the people who make them up, the group in Wuhan has a very active social life and we do a lot together. We hold barbecues, go out drinking, have days out in the city and take trips to other places in China, not so much as a group forced to be together by expediency but as a group of good mates. Perhaps because only a few kinds of people choose to move so far around the world, or perhaps because of pure happenstance, but I get on really well with most of the other foreigners who live out here. We do stuff pretty much every weekend and enjoy each other’s company. As well as the social aspect, we often help each other out with tips on job offers, new places to check out and advice on how to deal with some of the trickier aspects of life out here. A good example is one of the best experiences I have had living here – a holiday a couple of other teachers and I took to South East Asia during the Spring Festival holiday. We had a great time and all found the experience a lot easier than it would have been if we had attempted it alone. It’s tough for Chinese people to pay for and get Visas for trips abroad, so expats are pretty much your only option for company on trips outside of China. Without the expat community, my life out here in Wuhan would be a lot more boring. This isn’t to say I don’t have Chinese friends – I do – but rather that I do rely on other foreigners for a significant proportion of my social life in China.

Although being part of the expat community in China has been a really rewarding experience, there have been parts of it that I found problematic. The first isn’t really the expat community’s fault, but it is a problem I associate with it. When you have the option of spending time with other English speakers, it can be very tempting to spend basically all your time with them and not bother getting to know any of the locals, which to my mind would be a mistake. One of the things I have enjoyed most about living in China has been getting to know and becoming close to some Chinese people. This has both deepened my understanding of the society I am temporarily part of and given me the spice of some variety in how I spend my time. Some of the expats I know out here have very few or even no good Chinese friends, although most have at least a couple. This is more of a personal thing than a problem with expat communities themselves, but it is very easy to fall into the trap of only spending time with other foreigners.

Another problem, which has much more to do with the intrinsic nature of an expat community, is that it can be quite difficult to deal with any problems that arise between people within the group. Expat communities tend to be pretty small, but in the less Westernised parts of China they can be tiny. The group I’m part of in Wuhan has around thirty regular participants and although there are a good number of other foreigners who aren’t in this particular group, based on my experience I’d say we represent a significant proportion of the total number of foreign teachers currently living in Wuhan. This means that fallings out or misunderstandings between individuals tend to affect the entire group and can prove difficult to resolve. I have noticed that there is a slightly worrying tendency to just ostracise people who most of the group find annoying or don’t get on with, which doesn’t really fit with the friendly, open picture I painted of expat life in the above paragraphs. I guess it would be fair to say that expat communities are great if you fit in, but if you have trouble with this then you are not going to have such a good time. This happened to one guy I know after he got really drunk at a party and irritated the hell out of everyone by stripping off and refusing to leave or put his trousers back on. He wasn’t particularly well liked anyway, so even though this wasn’t that bad, he got ignored a lot after that. Although this is understandable – the groups are so small that it is fairly easy for someone to get on the wrong side of most of the expats they know – it still sucks if you are the guy being pushed out. As well as this, when disagreements occur between people who are usually pretty close it can get nasty. Again, it is the size of the group that is the problem – it is very hard to avoid someone to let them cool off when basically all your mates are their mates too. The longer I have been here the clearer it has become that I know basically every other foreign teacher here and am only one degree of separation away from the ones I don’t know personally. This means that it isn’t really an option to give someone a little space – you inevitably have to either deal with the problem, which isn’t always easy, or risk messing up the whole group’s dynamic. This happened to a couple of my friends recently – they got in an argument during a poker game which escalated when neither proved willing to back down and lose the pot. They rest of the players inevitably took sides and the whole thing got pretty heated. At the moment those two don’t really want to talk to each other, but are struggling to avoid seeing each other and have been consistently snappy and aggressive when they do talk. Back home they could have taken a little time to cool off, but that is a lot harder to do when you are both part of the same small group of expats.

Despite the problems I have occasionally encountered with being part of the expat community in Wuhan, I have really enjoyed being part of its expat community. Basically, we are all in pretty much the same position and the impulse to make friends and help each other out generally overcomes any problems you might have with the groups other members. For me, there was one person I didn’t much like when I first met him but spent time with anyway because we were both part of the same relatively small group and after a while, I found I had started to genuinely like them. Being an expat is a foreign city is a once in a lifetime experience for a lot of people and for me at least, it has been one that was greatly enriched and improved by being part of a wider community of foreigners.

Adam Lorimer, English Writing Teacher, Wuhan Donghu University

How to Prepare for China

By Frances Upton, long-term teacher in Wuhan.

With many people planning on heading out to China for the summer, or starting on the long-term programme in September, I’ve been thinking about advice I can give to anyone who’s planning on TEFL-ing in China; such as, what to bring and what needs to be done do to prepare, both physically and mentally.

China is a pretty daunting place, especially at first, so I tried to prepare myself as best as I could by scouring the internet for other blogs that might offer some insight into What It’s Really Like. Inevitably, no matter how vigilantly you prepare, you will be hit by many many ‘unforseens’. So I thought I’d share my experiences so far and write a kind of guide on how to prepare for a move to China, be it just for the summer or a bit more long term like Alex and I.

First of all, the boring bits:

The Admin…

Visas (paid teaching programme only)

We had a lot of time to psyche ourselves up for China due to many frustrating visa delays (trying to get your visa around Spring Festival time in February takes significantly longer than the rest of the year). Usually I think it’s a pretty quick and easy process. Teach English in China were really helpful with explaining the whole process, as well as being on hand to reassure us whenever I panicked that it was taking so long (which of course was several times).

Basically, how it all goes is; after you’ve emailed all the required documentation to your employer (signed contract, medical form, passport copy, CV, and copies of your degree certificate etc), they send you an invitation letter and a foreign expert certificate via post. We thought this would take up to 10 days and were pretty surprised when it only took 3 or 4 to get to us. Then we filled in the online form and booked an appointment at the Chinese Visa Application Centre in Manchester, submitted all our documents, bit my fingernails for 2 days convinced (for no reason in particular) that we’d get rejected, then collected it on the 3rd day. We booked our flights within 2 hours and were on the plane to China in 3 days! It was pretty crazy how quick and easy it was once we’d received the documents.

But it doesn’t end there…

In-China admin (paid teaching programme only)

The visa business doesn’t end with the pretty looking new page in your passport permitting your entry into China. This expires within 30 days, which you then have to convert into your Foreign Experts Permit and Working Visa once you get here. The school helped us with all of that. The only things we had to do ourselves were; registering at our local police station once we had our apartment address and doing a medical check (dead easy, don’t worry too much about that. They just want to make sure you don’t have any contagious diseases or serious conditions).

Once they’re done, someone from your school will take you to the Public Security Bureau (PSB) where you fill in some forms, and voila! A few weeks later you’re officially an Expat in the PRC!

Travel Insurance

Most schools provide some sort of medical cover but you will need your own policy. We went with a long stay worldwide cover for just over £200 for the both of us with Alpha Travel Insurance.

Flights

We spent quite a lot of time hunting round for the best deals for flights to London, and after considering booking with a travel agents, we found it was much cheaper on Skyscanner.com. However, be warned that the price listed isn’t necessarily how much it’s going to cost you as sometimes the flights aren’t updated instantly. We booked ours through a company called 9Flights listed on Skyscanner, and flew over with China Southern. One-way flights are usually anything from £400-£600.

‘Qian’ (money)

We spent a few weeks leading up to China looking around all the travel agents for the best Pound – RMB (Yuan) exchange rate and then found that the best way to do it was to order our currency online. We found a pretty good website called www.iceplc.com which are really reliable and only took 3 or 4 days to get sent to us via recorded delivery. The exchange rate at the time (March 2013) was 9.2 RMB to £1…Obviously this changes.

Try and bring as much money as you can with you. Our company recommended that we brought around £800-£1000 (*for private schools that pay you a housing allowance and you rent your own place. If the school provide accommodation you do not need money for a deposit, so brining a bit less is OK in that case) for the initial month and a bit until our first pay cheque. I’d say bring a bit more if you can. Everything’s ridiculously cheap over here so if you’re clever and budget properly then you’ll be okay. If you’re doing a long-term contract and if your school don’t provide accommodation, like ours doesn’t, then you’ll need enough money for a deposit and usually landlords will ask for you to pay up to 3 months rent at a time. It sounds like a lot, but rent is very cheap over here compared to UK prices!

We also didn’t know until we got here that we’d be able to use our UK bank cards so easily. And as far as we know, the charge was only around £1.50. You’ll need to make sure that you tell your bank that you’re going abroad beforehand though, otherwise it will most probably get blocked.

The More Practical Planning Aspects…

Whenever we go away, I always buy a Lonely Planet book and a little pocket phrase book. It actually might be the most fun part of it all. The Lonely Planet China book is a bit of a brick but it has everything you need to know about every province in China.

Language

The phrase book was initially a pretty good buy and lived in my handbag for the first month. But when you’re living somewhere, you can’t really keep resorting to a little touristy book. Plus, you’ll definitely pick up much more Chinese than you think if you just put your mind to it. Having Chinese friends and getting to know people at work helps a lot. For the slightly awkward, cringy moments when you find yourself gesticulating wildly to a shop assistant mumbling English that you know they can’t understand like a mad woman, the TrainChinese app for iPhones (and I think Androids too) is an absolute life saver. It’s only really good for words rather than full sentences though, so I wouldn’t rely on it too much. Also, it offers no help whatsoever on The Dreaded Four Tones.

If you have enough time before coming to China, I’d say try and get on an intensive Chinese course for a few weeks, just to begin to ease you in a bit. I had ten lessons at Uni last year which helped a little, and also Rosetta Stone is really good.

Clothes & Cosmetics

Fella’s – if you have big feet, stock up on shoes back home! The biggest we’ve found so far is a 43 (around an 8 or 9). It is possible to find bigger sizes if you know where to look, but I’d bring a good few pairs just in case!

Ladies – Cosmetics in China are on the whole pretty expensive. You’re looking at £30+ for average foundation and £50+ for a decent bottle of perfume. Stupidly, I’d assumed I’d be able to find my colour foundation out here, but having darker skin than most Chinese women, it’s pretty much impossible, so I ended up asking my sister to send over several bottles good ol’ Maybelline, but postage really isn’t cheap so stock up before you leave!

Also, probably the most important thing for girls. (Sorry guys!!) It is not a myth, finding tampons over here is pretty much impossible. Before I came out, my mum and I stocked up on what we estimated would last about 6 months, which got me a really funny look from the cashier in Boots, and I’m sure Security had a good giggle when my bag went through the scanners at Heathrow. We were way off so just bring more than what you think is LOADS.

One thing we found when we arrived, was that although our contract had said the dress code was ‘smart’- i.e shirts, ties and smart trousers for guys and smart trousers and skirts for girls, when we went into work for the first time we found everyone dressed really casual in jeans and t-shirts. The most annoying part was that we’d used up so much of our suitcase space bringing all our smart clothes, plus more that we specially bought, which we haven’t even worn once. So my advice is check with your school beforehand what the dress code actually is.

Other very important things…

If you love Haribo as much as I do, stock up as much as you can. And chocolate. Although you can find it here, it’s not the same, just Snickers, Hershey’s and Dove (Galaxy).

Also, now, I feel pretty ashamed actually writing this, being fundamentally against any form of e-readers since they came out, but if you don’t have one and you read as much as I do, get a Kindle. I haven’t been able to find a single bookshop in Wuhan that sells English novels (although I am assured rather elusively that there are a couple…). And apart from bringing three of my favourite books over, I’ve had to resort to stealing Alex’s until mine arrives.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube and most blog providers in general are all banned in China, but if anyone’s interested, there’s a really good iPhone app called ‘VPN Express’. Skype’s the best way of keeping in contact with people back home. But most people in China use WeChat and QQ to communicate out here so make sure you get an account.

Don’t forget mains adapters! European mains adaptors work as well as the Chinese variety.

What to Expect

All these things will help you prepare for China as best as you can, but there are certain things you’ve probably heard about. Just make sure you expect them, because as what often happens, reality will not match up to your expectations. It’ll be daunting at first, as it still is for us sometimes, because new things always are a little scary.

1. People will stare at you from the minute you step off the plane. Just smile and say nǐ hǎo even if all you want to do is run away back home!

2. People spit. A lot. And everywhere. It’s not even just spitting, it’s proper hocking like you’ve never heard before. Waking up to the sound of your neighbours morning phlegm just becomes part of routine.

3. Squat toilets aren’t as bad as you think. Some can be beyond vile, but again, on the whole, you just get used to it. Also, take tissues with you everywhere, as they don’t provide loo roll in public toilets.

4. Come to terms with the fact that milk and cheese will no longer be such a big part of your life. You can find it, but it’s pretty expensive and just not the same.

5. Chinese food is absolutely nothing like Chinese food back home. We’ve found one place where we can get Sweet and Sour Chicken, but apart from that, especially in Wuhan the food is really spicy. It’ll take a bit of getting used to, particularly while you master The Art of Ordering, but it actually is great!

Most importantly though, have an open mind and be brave. Just try and experience as much as you can in your time here; there is so much to see and learn about China. Because like we’re learning only much too quickly, your time will fly by over here!

By Frances Upton

The teacher-student relationship: Language learning and practice beyond rights and wrongs

The purpose of this article is to cast some light on the issues surrounding how to manage the student/teacher relationship in China, and how to overcome the conflict within language learning between the need to maintain ‘face’ and the need to make mistakes.

Playing with Power:

Students will generally default to treating the teacher as an authoritative figure. Obedience and respect towards one’s elders are fundamental to Chinese culture, as laid out in the Confucian principle of ‘filial piety’. This relationship can also be traced back to early prescriptivist teaching methodologies that were based on translation and the acquisition of grammatical rules. Here a teacher would stand at the front of the class and dictate language rules and structures to the students:

‘Typically, Grammar-translation methods did exactly what they said. Students were given explanations of individual points of grammar, and then they were given sentences which exemplified these points. These sentences had to be translated …accuracy was considered to be a necessity.’ (Harmer, 2007 p.63)

Unlike communicative activities, when it comes to grammar there is usually a ‘right’ and a ‘wrong’. Saying ‘I can have the bill’ instead of ‘can I have the bill?’ would likely result in you getting the bill, but the grammar is totally incorrect. What do we hate more than anything? Making mistakes. Making mistakes in front of peers, and even worse, making mistakes in front of an authoritative figure; a person able to instantly point out your fault. Here is an example of a teacher in China shaming a student by pointing out his faults for all to see:

The loss of face (as shown in the video) can be a horrendous experience. Anyone who has learnt a second language understands how easy it is to feel stupid, and misrepresented by your own lack of linguistic competence. As Helen Spencer-Oatey discusses within the context of rapport management, there is a lot at stake in one’s communications: interactional rapport (basically the perceived relationship between communicators) is affected by three main factors. Spencer-Oatey describes these as face sensitivities, sociality rights and obligations and lastly, interactional goals (Spencer-Oatey, 2000). I can’t go too deeply into this here, but basically we’re talking about how sensitive you are to looking stupid in front of others, and your right to maintain the integrity of your position (through an appropriate level of respect and obedience) within the context of a specific group of people (peers, colleagues, family).

Returning to the question of how to manage the student/teacher relationship, I think keeping this brief account in mind will help you to understand why, when addressing a question to the class, few will happily volunteer to stand up and pour their hearts out in the best English they can muster. I believe creating a warm, comfortable learning environment, and by subtly reducing the authoritarian vibe, you can get more out of the students and help them to take more risks.

Learning means taking risks:

In my teaching approach, I am proactively attempting to reduce the perceived relational distance between student and teacher. In some ways this is automatically achieved by virtue of the fact that I’m a bit of a spring chicken. However, by adjusting the register (formal/informal content) of my exchanges with the students, I may also proactively narrow (though not close) the gap. An example of this would be letting students address you with ‘hey’ instead of ‘good morning sir’.

My justification for taking this approach is as follows: language acquisition entails subjugation to a certain degree of risk (Harmer, 2007). The need to submit to such risk poses a significant challenge for students, particularly where sensitivity to face-loss plays a more prominent role in the wider cultural environment. The negative impact of face-loss is hightened where the event takes place in a public setting (amongst a large class of peers) and under the supervision of a credible expert or authoritative figure (teacher), as mentioned.

Though the presence of a power differential between student / teacher is unavoidable, by reducing the gap through affective and linguistic efforts, the pressure associated with making mistakes in front of peers and teacher alike may be softened. Examples of such behaviours include demonstrating a mutual understanding of the difficulties of language acquisition (in my case I’m struggling with the students’ L1, mandarin), and deferring face loss through paired or group work, where contributions are resultant of a group effort. You could also wear more casual clothing (where permitted), express your own opinions, share aspects of your own life (generally show that you’re human and not a walking textbook). Simply being relaxed and allowing students and oneself to laugh at errors may also help to cultivate a submissive attitude towards the inevitability of errors. In this way learning becomes more enjoyable for all involved.

Let’s see what happens over the next year!

References:

Harmer, J. The Practice of English Language Teaching. 4th Edition.

Spencer-Oatey, H. 2000. Culturally Speaking: Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory. Continuum: London.

Other useful sources of information:

British Council EFL Teacher Manual.

Cook, V. Second Language Learning and-Language Teaching.

Cowan, R. The Teacher’s Grammar of English

By Daniel Legere, long-term teacher in Yueqing since September 2012

Being a Foreigner

By Frances Upton

One of the strangest things about moving to China is that out of the blue and without realising it, you have now become ‘the foreigner’. Almost daily we use the term ‘foreigner’ to put a name to the increasing presence of ‘other’ in our societies, particularly in the UK. But now, I’m not even sure I understand it at all. Who decides what’s foreign when people are moving around and exploring so much? In China, you can hear children and old women whispering ‘lǎo wài’ as you walk past, in Malawi, people will point and shout ‘mzungu’ at any white face they see. And despite always been on the fringes; mixed race, half and half; I’ve never really felt so much like a foreigner until now.

What got me thinking about all this was reading on BBC news about the attack on a soldier in Woolwich and reading the outraged response, particularly on social networks. People were throwing around the term ‘them’ and ‘they’, clearly referring to all Muslims, or all immigrants; ‘foreigners.’ I read a Facebook status which said something along the lines of ‘they come over here, take our jobs, use the NHS…’ an almost comical, clichéd attitude I’d always thought had been buried a long long time ago. It just made me think, two individual people do something horrific and unforgiveable, and then suddenly their whole race or their whole religion are all ungrateful, unwanted ‘terrorists’. They’re all ‘foreigners’ that have no business, no right to be in our country. It’s completely ridiculous. Two people did something horrific, and suddenly all foreigners are the enemy.

Right now, here in China, we’re the foreigners. Americans, British, Canadians, Russians: Foreigners. And I honestly can’t imagine anyone I’ve met so far in this beautiful country, which I’m almost beginning to see as a kind of temporary adopted home, being so unwelcoming and, well, cruel. Mostly, from what I’ve experienced so far, they love us ‘lǎo wài’. They smile and say ‘nǐ hǎo’ (hello), they try to speak to you in as much English as they can, and they’re always so helpful. We’ve made so many lovely Chinese friends over here who honestly don’t mind you calling them in the morning to ask them to speak to your building manager because there’s no water in your apartment, or taking you to the other side of the city late at night to pick up the extra key from your landlady because you’ve stupidly forgotten yours inside, or booking your train tickets for you because you can’t speak Chinese. It actually makes me pretty sad to think that back in the UK, if a foreigner can’t speak English, we’ll grumble and tut and think they have no business being in ‘our country’.

Above: Frances at Wuchang Riverside Park in Wuhan

I came here not able to say a single sentence in Chinese (although every day I am learning). But the Chinese value education, and because cultural exchange in this day and age is education, they value us too. Simply because our reason for being here is to teach them our language and to learn more about China and their culture, and in turn they can learn about ours. People here even seem to like the fact that I’m “mixed blood” because to have two races, two sets of roots is something to be proud of here. It makes you modern, it makes you worldly. It’s a source of pride.

It’s a lovely thing to feel so welcome, so wanted and valued. Sometimes it can get a little too much when you’re having a bad day and you want to just tip-toe through the crowds unnoticed (luckily for me, sunglasses seem to help me blend in a little better on days like those!). At work especially, all of the parents of the kids we teach want to see the ‘foreign teachers’, but once again its just pride rather than anything sinister. Having ‘real foreigners’ teaching at an English Language Centre makes it all the more credible and genuine.

Yesterday, Alex and I went to the famous Guiyuan Temple in Hanyang, snapping away like tourists and hanging out with the tortoises in the courtyard pond when this group of teenage Chinese girls approached us. They, along with their very embarrassed mother asked to take numerous photos with us. Who knows what they could possibly want or need with ten pictures of two very sweaty looking foreigners, but it happens all the time. Our American friend David went to the hospital a few weeks back for a chest infection and spent the afternoon being fawned over by several young Chinese nurses. If that wasn’t good enough, in the end he got his entire treatment for free because they asked him to model for some pictures for a hospital advertisement.

You get used to it, being a foreigner. But I can’t imagine what it’d feel like if, say a man from the US did something terrible over here and then suddenly everyone here turned on me too and wanted me to ‘go back to where I came from’.

I’m not saying there isn’t racism or anything like that in China, but in my experience, the greatest thing about being here is feeling so welcome. I really do think it’s something the rest of the world could learn from China. Although everywhere you go you will be stared at and sometimes it may even feel like you’re being judged in a negative way, I honestly do believe that over here they’re just curious. They want to know who you are and what brings you to their corner of the world.

The term ‘foreigner’ shouldn’t be used in such a negative way, because at the end of the day if everyone stayed in their own ‘designated area’, their own comfort zones, we’d all live in a very colourless and silent world. Each and every one of us is capable of good and bad, regardless of whether we’re ‘foreign’ or ‘not’.

By Frances Upton

China: As a foreigner, how are you treated? By Vijesh Parmar

I have been living in Wuhan, an up and coming city in Central Eastern China for the previous six months, working as an English Teacher at Wuhan Donghu University . One question, that I am frequently asked is “Ni lai zi na li?”, which translates to “Where are you from?”

I’m almost certain that this question is a lot less frequent in the bigger cities of Shanghai and Beijing, since the foreigner population of those two cities far exceeds that of Wuhan. One thing that is certain, is that the Chinese, in my experience at least have a natural fondness for foreigners and an element of loquaciousness, a willingness to ask questions, about anything and everything relating to your country. For myself after a little while I knew which questions were going to be asked. The more common ones such as “Where are you from? Are you accustomed to China? Do you like Chinese food?”, to the less frequent ones such as “Do you have Falun Gong in your country?”(Falun Gong is a banned activity in China, for political reasons).